Julita Manor’s history

Monastery, royal estate, artillery foundry, noble estate, and manor house. Julita Manor has a long and rich history and is today a cultural-historical excursion destination preserved by Swedish museum Nordiska museet. Here you’ll learn more about Julita Manor’s history from the 1180s to 1941.

Royal Estate and Monastery in the 1180s

Julita Manor is an estate located by Lake Öljaren, within barely a two-hour journey from Stockholm in the province of Sörmland.

The oldest document mentioning Julita dates back to the 1180s. Julita was then a royal estate and was referred to as Säby, the village by the lake. The document is signed by King Knut Eriksson and proves that he granted the royal estate with “houses, fields, fishing waters, forests, meadows, and pastures” to a group of monks in the Cistercian order.

They had been settled in Viby, outside Sigtuna, for twenty years. The monks moved to Säby and founded the Cistercian monastery of Saba (a Latinized version of the name Säby). The monastery was active for about 350 years.

The last time Julita is mentioned as a functioning monastery is 1525. Even today, you can descend into the preserved medieval vaults and see the monks’ skill in building with brick.

Royal Estate in the 1500s

In 1526, King Gustav Vasa passed a resolution in the Riksdag that the crown should take over the wealth of the monasteries.

The following year, the Västerås Parliament decided that the Catholic monasteries in Sweden should cease to exist. Julita reverted to the crown and became a royal estate. Large parts of the monastery buildings were demolished, and new houses were erected. Jöran Persson, King Erik XIV’s advisor, lived here for a while.

Gustav Vasa’s youngest son, Duke Karl of Södermanland, had a son with his mistress Karin Nilsdotter. Their illegitimate child grew up and attended school at Julita. He later became known as Admiral Karl Karlsson Gyllenhielm.

Duke Karl later became King Karl IX, and after his death, his widow Kristina received Julita Manor as a widow’s seat until her death in 1625. She belonged to the German Holstein Gottorp dynasty, and her coat of arms has been found beneath the plaster on the Southern Wing.

Artillery Foundry in the 1600s

In the 1600s, there was an artillery foundry at Julita. The Thirty Years’ War was raging in Europe, and there was a great need for cannons. The Austrian artillery officer Melchior Wurmbrandt came to Julita in the late 1620s. He had developed a light cannon, the so-called leather cannon, which was easier to handle in the field than the heavy cast-iron cannons.

King Gustav II Adolf became interested in the invention, and Wurmbrandt was granted Julita to start cannon production here. (Whoever granted a estate received taxes from the farmers who cultivated the estate’s land, instead of the tax going to the state.)

The assembly of Wurmbrandt’s cannon took place at Julita. However, the leather cannon did not become the success in the field that everyone had hoped for. Lack of information led to it being overcharged and bursting. Wurmbrandt later participated in the war and was captured in 1636. After that, his fate is unknown.

The Austrian Paul Khevenhüller (1593–1655) served under King Gustav II Adolf during the war. A lot of money was spent during the war, and Khevenhüller lent 70,000 riksdalers to Gustav II Adolf, a very large sum of money at that time. When Gustav II Adolf was killed in battle, Khevenhüller went to Stockholm to get his loan back. Instead of money, he received Julita as collateral.

The estate was then much larger then than it is today. It included the entire Julita parish except for the estate of Gimmersta. Khevenhüller never moved to Julita. He leased out the artillery foundry to the Dutchman Henrik Trip. And around 1660, the ore began to run out. The forests were plundered to obtain charcoal for the foundry, but it became unprofitable and was closed down.

Noble Estate for the Palbitzki Family in the 1600s-1800s

When Khevenhüller’s daughter Anna Regina Khevenhüller (1618–1666) married Mathias Palbitzki (1623–1677), Julita came into the possession of the noble Palbitzki family.

Mathias Palbitzki came from Poland and worked as a diplomat and art dealer for Queen Christina. He traveled extensively throughout Europe and also visited Egypt.

During his travels, he made numerous drawings, and in his surviving sketchbooks, there are several interesting sketches of Julita from the 1650s. They show the medieval buildings of the Southern Wing and the Abbot’s House, ruins of the other monastery buildings, two large timbered residential houses, and several smaller cottages. Mathias Palbitzki spent his last seven years at Julita.

After him, his son Alexander Palbitzki (1660–1724) took over Julita Manor. Alexander Palbitzki kept a journal of tasks and events on the estate. They are meticulous notes on the number of animals, income from, for example, ox trading, forestry, agriculture, and fishing. Therefore, we can get a very good picture of how the estate operated between 1704 and 1724.

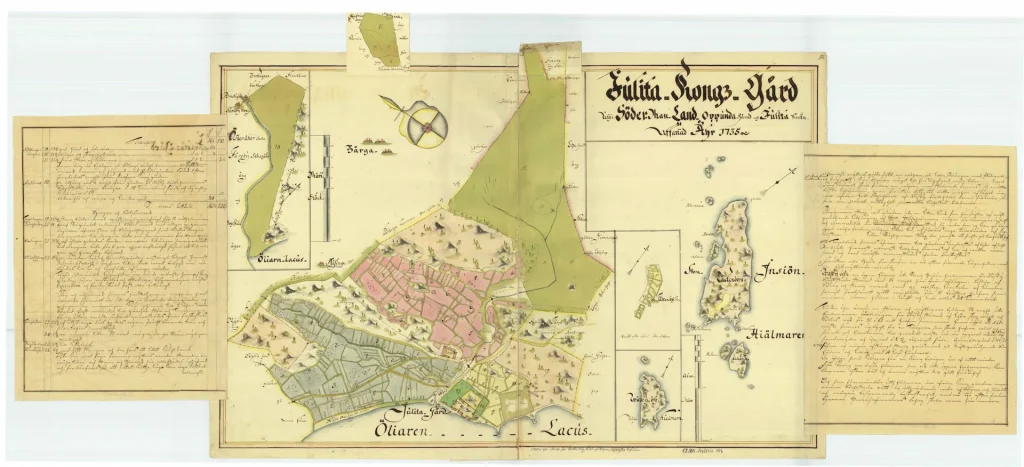

From 1735, there is also a detailed map of Julita, made by surveyor Mårten Rivell.

The next owner was Axel Gottlieb Palbitzki (1698–1760) along with his wife Charlotta Christina Siöblad (1693–1770).

They built an almshouse and a school in 1742. The school was one of the first in Sweden. In 1745, the main building of the estate burned down. A new one was completed around 1760.

The last Palbitzkis at Julita were Matthias Palbitzki (1782–1851), the grandson of Axel Gottlieb Palbitzki, and his wife Beata von Ungern-Sternberg (1788–1872) from the neighboring farm of Äs.

Beata Palbitzki was a very compassionate woman who showed great care for the people on the estate. They had no children, so after Beata Palbitzki’s death, distant relatives inherited Julita. They decided to sell the estate.

The Bäckströms at Julita 1877-1941

In 1877, the tobacco company W:m Hellgren & Co bought Julita. The company owner Johan Bäckström (1826–1902) was born in Umeå, where his father Anders had become wealthy in the timber trade.

During the last decades of the 19th century, Johan Bäckström made significant investments to rationalize agriculture. The increasing need for labor led him to employ more farmhands. Grain imports to Sweden increased during this time. This made domestic grain cultivation unprofitable. Therefore, he focused agriculture on cattle farming and dairy processing. Johan Bäckström married the beautiful Lilly von Ehrenclou (1840–1901, in the picture) and became the father of five sons.

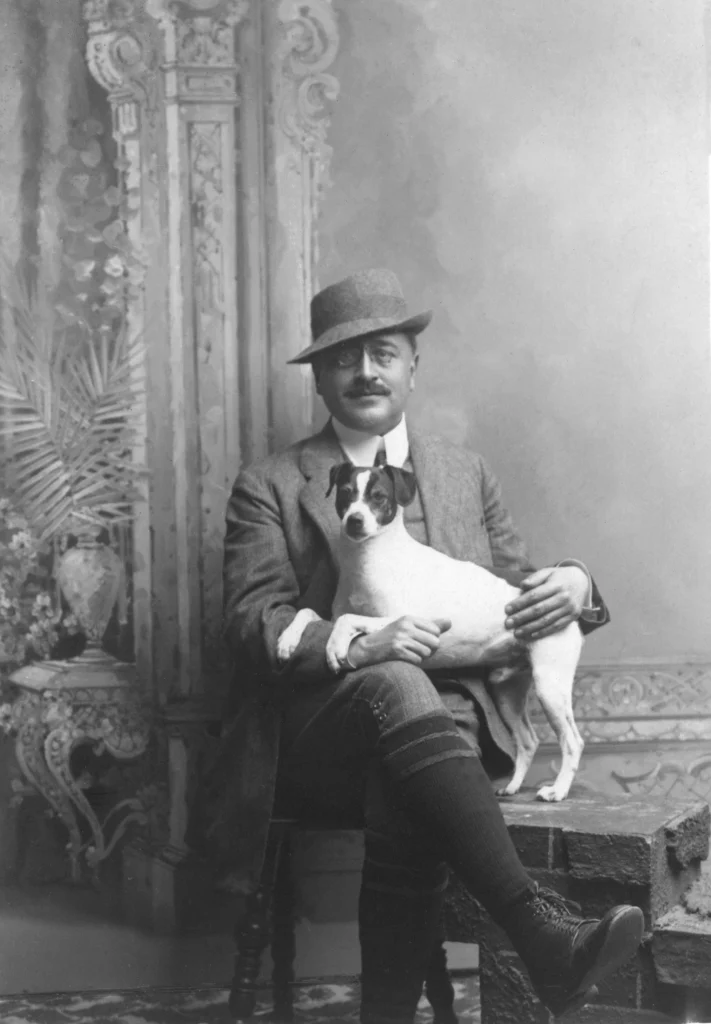

One of them was Arthur Bäckström (1861–1941). Arthur Bäckström is the last private owner of Julita. He served in the Sörmland Regiment and was a lieutenant when he left the army in 1906. Arthur had leased Julita since the 1890s and inherited it in 1902.

Nordiska museet owns and preserves Julita Manor since 1941

Arthur Bäckström had no children and bequeathed Julita Manor to the museum Nordiska museet in Stockholm. The Nordiska museet Foundation took over the estate and grounds after his death in 1941. Since then, Nordiska museet preserves Julita Manor as it was when Arthur Bäckström lived here and has made it accessible as a cultural-historical excursion destination.